Facing the Truth: We are not so good at recognizing faces

This is the first part of the 3-part series on face recognition. This blog post is dedicated to explain how we greatly overestimate our face recognition capability and why we might need machine's strength in recognizing faces. Part II aims to remove the mystery around face recognition, and explains how you can apply it to your own business case. Finally, in Part III, privacy by design will be discussed under the light of new General Data Protection Regulation coming into force May 2018.

Did you notice that you are extremely good at spotting your co-nationals when abroad? Did you ever question why it is substantially more difficult for you to distinguish one Asian national from another than your Asian friend? Did you feel embarrassed when someone was excited to see you AGAIN, but you have no clue who that person was? If yes, read on – this series on face recognition is for you.

1. The DiCaprio Phenomenon

Face recognition is a crucial skill for us, humans. It meant life or death for our hunter-gatherer ancestors to be able to separate a member of the hostile neighboring tribe from a friendly face of their own. Therefore, evolution gifted us with regions in our brains devoted to recognizing faces. We score close to perfect given variable conditions such as distance, illumination, occlusion when it comes to recognizing celebrities, our significant others, family members and other people we interact with frequently.

You must have seen images of Leonardo DiCaprio as a young man and as he is today. When I ask you, if these set of images belong to the same person, you would quite confidently say yes, and probably name the person as well: Leonardo DiCaprio! Although there are some 20 years and maybe 20kgs (no offence if you are reading this, Leo) between these images, it is an easy task for us. We have seen him in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, Titanic, Departed, The Revenant and many other films. His face is known to us. I call this the DiCaprio Phenomenon. Based on our success of recognizing likes of Leonardo DiCaprio, we assume that we are pretty good at recognizing faces in general. Are we, really?

Skeptical and/or curious about the DiCaprio Phenomenon? We created a simple game where you can put your face recognition skills to the test. You will decide if the two images presented to you belongs to the same person or not. In the dataset, there are celebrities that you might know. As you go through the test, think about the cues you use to recognize faces. Does it get easier when you know the person? Do you feel the wheels of your brain turning at an unprecedented rate when the person in the image is not so familiar?

Now that you have tested your skills, let’s dig deeper. In the ‘Losing Face’ episode one of my favorite podcasts, Mike Burton, Professor at the Department of Psychology at the University of York, revealed that when it comes to recognizing faces of people we don’t know, we are quite often inaccurate. He and his colleagues set up an experiment in both UK and Australia. They asked people to tell if the two facial images presented to them belong to same person or not. Their image set consisted of images of Australian and UK celebrities who are famous locally but not so much internationally. Participants from UK matched their local celebrities with great success and performed poorly on Australian celebrities whereas Australian participants were great at matching their local celebrities but failed to do so with UK celebrities.

Things become even more interesting if you add confirmation bias to the shortcomings of our face recognition capabilities. In this case; when the participants were asked, participant from UK thought that other people would easily recognize UK celebrities whereas Australians suggested that Australian celebrities would be easier to recognize.

2. What about Professionals?

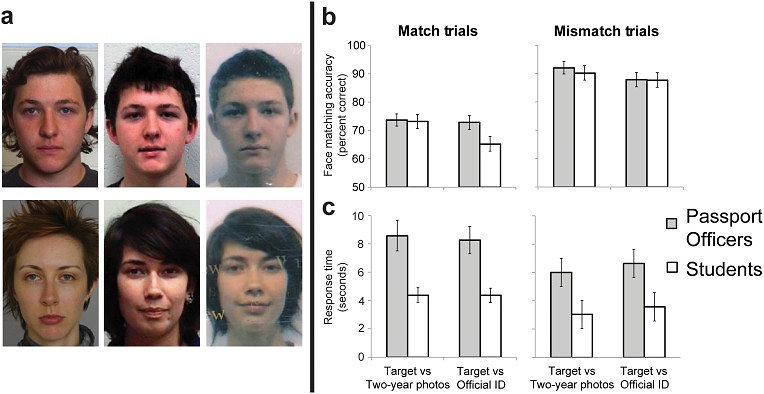

Most of us operate with the assumptions that professionals are good at matching our faces. Let’s take the border control for example. We tend to assume that the officers at the border control are pretty good at matching our face with the photo in our passport. You may see where this is going: Yes, even the professionals are bad at recognizing unknown faces. Passport officers find recognizing unknown faces difficult and are quite often inaccurate. In a study made by White et al. 2014 passport officers barely outperform randomly selected students. The 75% face matching accuracy was recorded for passport officers during match trials as shown in the figure below.

Fig.1 (a) match pairs(top), mismatch pairs(bottom) Left column target photo, middle column 2 years old photo, right column ID photo (b) Mean Accuracy (c) Response time. (White et al. 2014)

The match rate, of 75%, lower than expected, in spite of the long response time of 8s on average. Passport officers need to process high volumes of passports in short time frames. White et al. elaborate that, a key performance target for British Passport Officers is to process 95% of passengers from the European Union and European Economic Area within 25 min of joining a passport-control queue on arrival. Similarly, Australian passport officers aim to process 92% of passengers within 30 min. In their research, passport officers matched the faces under time pressure varied between 2 to 10 seconds and 2 to 8 seconds. Both experiments showed a significant deterioration in the face matching performance under time pressure of 4 seconds or less.

We are vulnerable to more biases than the ones explained so far, e.g. bystander apathy, tiredness after a long shift, and the need for multitasking the factors to further decrease our ability to recognize faces. In fact, in a real-life case, we are seldom asked to match faces only. Age check for alcohol sales, validity check for a driving licence, or biographical data verification for passport for example. Knowing this, Burton and Mccaffery (2016) studied the impact of biographical data verification on face matching performance of passport officers. It was shown that the presence of a passport frame as shown in the figure below leads to significantly worse performance. An example of this can be seen in the figure below.

Fig.2 Images from Glasgow Face Matching Test as it is and embedded in a passport frame (Mccaffery & Burton 2016)

This pattern of data suggests that the presence of a passport frame introduces a bias to respond ‘same’ to face pairs—a bias which will lead to increased errors in accepting fraudulent passports. This means that the security systems that we rely on in access control or any touchpoint that require visual confirmation of the identity is fundamentally unreliable. This might sound a bit worrying, but we have been already working on face recognition algortihm that could help us make better decision.

3. Is Computer Vision the Silver Bullet?

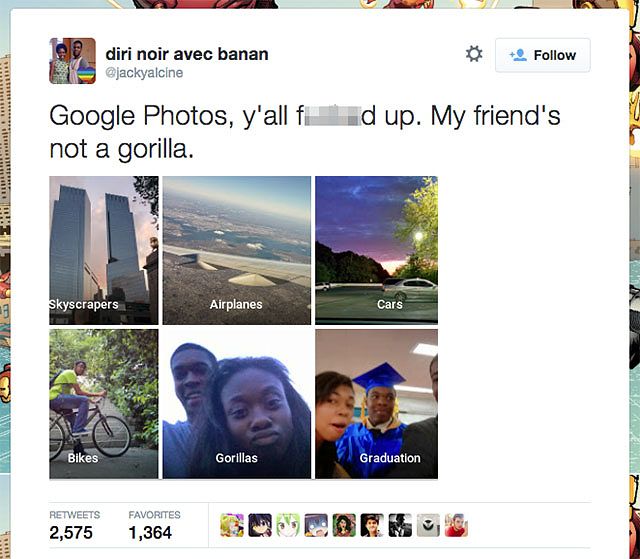

No, it is not. On the contrary, computer vision might have similar vulnerabilities and biases to us. Have you ever heard about the notorious Google object recognition which went horribly wrong? See in the figure below.

As you see, face/object recognition algorithms can strike us as racist and upsetting, as its recognition skills will be as good as the data it is trained with, just like our recognition skills. Remember how good we are at recognizing our co-nationals and not good at all distinguishing nationalities that we were not exposed to when growing up. Some of us are better at recognizing faces than the rest of us, just like algorithms can be better from one another. In the next blog post, I will explain the surprising similarities of the working principles of human vision and computer vision, and how to avoid mistakes like the one that Google made when choosing your algorithm. Tune in for understanding use cases for face recognition, with real life examples. I will also cover guiding principles that will help you decide which hardware and algorithm combo might work best for your use case.

If you have taken the test and were surprised by the result, or have a burning desire to prove me wrong just send me an email and let’s have a chat!

*The DiCaprio Phenomenon: Please take precaution when using this term in public, as it is something I came up with! He is a great actor and activist, though the guy deserves a phenomenon named after him – especially after that pity Oscar he was given.

Tuğberk DumanHead of Innovation

Tuğberk DumanHead of Innovation