Using Cycle.js to view real-time satellite test data

A special guest post from Jan van Brügge, self-taught programmer, who makes everything from Cycle.js web apps to satellite control software. Jan is speaking at CycleConf next month, which is organised by Futurice and will take place in Stockholm.

This article assumes you are familiar with Cycle.js. If not this is probably fine if you know reactive streams like RxJS, otherwise check out the excellent documentation first.

The goal

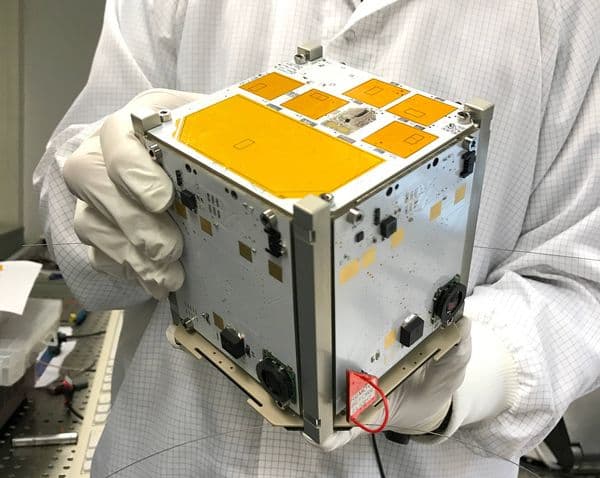

I currently work on the MOVE-II CubeSat, more specifically I work on the ADCS - the Attitude Determination and Control System. This means we have a small satellite packed with various sensors like magnetometers, gyroscopes and sun sensors. Those sensors are used to drive the control algorithms that drive our coils to actuate our satellite.

For tests we mount our ADCS PCBs to a 3D printed structure and hook them up to a BeagleBone Black Wireless - a small computer like the Raspberry PI - which emulates our main computer (the CDH system). We then suspend the satellite inside a Helmholz cage where we can provide an arbitrary magnet field that should simulate the earth's magnetic field. We then use the SPI connection of the BeagleBone to poll the sensor and control data from our hardware.

My goal is now to create an app that can be used to display the live data of our satellite while we are running the tests.

Step 1: Evaluation

Why use Cycle.js? I have multiple reasons. For one I work daily with Cycle.js and simply enjoy the concept and the readability of the framework. But the main reason is that Cycle.js excels at modelling complex, time based asynchronous behavior, which we are going to exploit.

The other piece I need for the project is the plotting of the data. For this task we will use the amazing d3.js library, because - as you will see later - it is a really good fit and addition to Cycle.js.

For the transmission of the real-time data we will use normal websockets wrapped by a custom driver.

Step 2: Let's begin

So the first step is to scaffold a new boilerplate. Luckily thanks to create-cycle-app this is quite easy. I also want to use typescript so we'll use the one-fits-all flavor (shameless plug).

create-cycle-app adcs_plot --flavor cycle-scripts-one-fits-all

Step 3: First implementation

As we hold on to the golden rule of optimization - never optimize prematurely - we'll just write a first version. Let's take a look at it, we have three interesting files:

graph.tsx

graphs.tsx

websocketDriver.ts

The websocket driver is quite simple:

import xs, { Stream } from 'xstream';

import { WebsocketData } from './interfaces';

export function makeWebsocketDriver(url : string) : () => Stream

return () => {

return xs.create({

start: listener => {

websocket.onmessage = (msg : MessageEvent) => listener.next(msg);

},

stop: () => {}

})

.map(msg => JSON.parse(msg.data));

};}

As we are only getting data from the server and not setting data, we just wrap the onmessage function in a new Stream.

The graphs file is just passing some settings to the graph file, we tell the name of the graph, the axis label, the domain of the incoming data (here we expect data between 0 and 100 degrees Celsius) and a filter, so we can extract the data relevant for this graph from the global state object.

import { Stream } from 'xstream';

import { Sources, Sinks, Component } from './interfaces';

import { createGraph } from './graph';

export function Graphs(sources : Sources) : Sinks {

const tempSinks : Sinks = createGraph({

heading: 'Temperature',

yScaleText: 't in °C',

yDomain: [0, 100],

dataFilter: data => Object.keys(data.temp).map(k => data.temp[k])

})(sources);

return tempSinks;}

So the magic all happens in the graph file. Let's discuss it in small steps.

export interface GraphInfo {

heading : string;

yScaleText : string;

yDomain : [number, number];

dataFilter : (d : WebsocketData) => number[];}

export interface Scales {

x : ScaleTime<number, number>;

y : ScaleLinear<number, number>;}

export type DataPoint = [number, number];

The first definition should look familiar. This is just the settings we use with createGraph. The second one is the definition of our d3 scales (more on them later) and the last one is just an alias for a (x, y) coordinate.

const scale$ : Stream

x: scaleTime()

.domain([new Date(), hoursAgo(2)])

.range([0, 500]),

y: scaleLinear()

.domain(info.yDomain)

.range([0, 500])});

Here is the first part that needs actual explanation. The code you see here is using d3's scales. With d3 version 4, the whole library was split into smaller submodules like d3-path, d3-shape or d3-scale which we used here. This has the great advantage that the calculations and the DOM manipulation is now clearly separated. As Cycle.js uses virtual DOM diffing under the hood we don't want external DOM manipulations.

A scale is just a normal Javascript function that takes some data and returns only the scaled data and does nothing else (pure functions - yay!). To initialize the function we use the .domain() and the .range() functions. The domain is the expected range of incoming data, the range contains the outgoing pixel values.

This means here we are creating two scales, one for the x axis and one for the y axis. The x axis is using a time scale because we want our data to be associated with the timestamp it was generated. The leftmost value on the graph should be the current time, the rightmost value should be two hours ago. We want those values to be mapped to a 500 pixel wide graph. The y axis is analog to the x axis, the only difference is passing the domain from the settings.

const scaledData$ : Stream<DataPoint[][]> = xs.combine(scale$, state)

.map(([scales, arr]) => arr.map(data => {

const x : number = scales.x(data.time);

return info.dataFilter(data).map(y => [x, y] as DataPoint);

}));Here we use our newly created scales for the first time. We combine our scales with the current state that is holding the data we get through the websocket. As we have multiple lines per graph (x/y/z part of a vector or something similar) and the timestamp of them will be the same, we first apply that scale to the timestamp and save it in a constant. We won't modify it.

For the y value we apply the data filter we pass in with the settings and then map the values (think here as [x, y, z]) to include the timestamp ([[t, x], [t, y], [t, z]]).

Now that we have the values of the pixels on the screen we want to display them. One option would be to just map the scaled data to svg <circle> elements, but I want to have lines between the points, so you can follow the data changes more easily. For this reason we will use a <path>. We could have used a <polyline> too, but d3 makes working with paths really easy. The module that is responsible for this is d3-shape. So we'll import { line } from 'd3-shape' and call it with our data points. The lines function generates a string that has to be used as the mysterious d attribute of the <path>. Again as we have multiple lines per graph we have to nest our map calls.

const path$ : Stream<VNode[]> = scaledData$

.map<string[]>(data => data.map(arr => line<DataPoint>()(arr)))

.map<VNode[]>(lines => lines.map(s => <path d={ s } />));The last part of the file is pretty self explanatory:

const vdom$ : Stream

.map(paths =>

<svg viewBox="0 0 500 500">

{ paths }

</svg>

);We map the array of path elements to be embedded in an SVG element. If you are wondering what the HTML is doing in the Typescript file, this is JSX syntax that was made popular by React. You can learn more about JSX here.

Step 4: Enjoy! ...Or do we?

If you run the code now, you will notice that the performance is not great. And with not great I mean horrible. After the initial few data points the browser gets slower and slower and won't respond at all in the end.

Step 5: Making it better

We have to identify the issue with our code. Why is it so slow? One particular piece of code comes into sight:

const scaledData$ : Stream<DataPoint[][]> = xs.combine(scale$, state)

.map(([scales, arr]) => arr.map(data => {

const x : number = scales.x(data.time);

return info.dataFilter(data).map(y => [x, y] as DataPoint);

}));Let's take a closer look on our data processing. I have outlined the whole process below:

New data comes from the server:

{

accel: {

x: somevalue,

y: somevalue,

z: somevalue

},

... //Some other stuff

}

The websocket server adds it to the state array: [...oldState, newData] Notice that we are creating a new array here!

Then we run our data filter over the each data point which was defined as:

// info.dataFiler: data => Object.keys(data.accel).map(k => data.accel[k])

const scaledData$ : Stream<DataPoint[][]> = xs.combine(scale$, state)

.map(([scales, arr]) => arr.map(data => {

const x : number = scales.x(data.time);

return info.dataFilter(data).map(v => [x, scales.y(v)] as DataPoint);

}));const path$ : Stream<VNode[]> = scaledData$

.map<DataPoint[][]>(data => data.reduce((acc, curr) => {

return curr.map((p, i) => [...(acc[i] ? acc[i] : []), p]);

}, []))

.map<string[]>(data => data.map(arr => line<DataPoint>()(arr)))We have the arr.map that creates again a new array (every time we update our data) and the dataFilter plus the map create x times two new arrays, where x is the number of data points. The reduce alone creates a bazillion arrays in the process.

That is a lot of allocations for the Javascript engine. You can see this also when profiling, the heap is building up rapidly and has to be GC'd quite often.

So how can we make this better? We write a new version.

Let's ask a simple question. Why are we storing our state as array of data slices? If every line of every graph needs an array of data values, why not store them as such?

function foldData(acc : State, curr : WebsocketData) : State {

const flatData : [Date, number][] = flattenData(curr)

.map(d => [curr.time, d] as [Date, number]);

const values : [Date, number][][] = acc.values.map((data, i) => [flatData[i], ...data]);

return {

values: values

};}

function flattenData(data : WebsocketData) : number[] {

return [

data.accel.x, data.accel.y, data.accel.z,

data.gyro.x, data.gyro.y, data.gyro.z,

data.magVector.x, data.magVector.y, data.magVector.z,

data.sunVector.x, data.sunVector.y, data.sunVector.z,

data.temp.bmx, data.temp.t1, data.temp.t2, data.temp.t3,

data.magRaw.x, data.magRaw.y, data.magRaw.z, data.magRaw.r,

data.sunRaw.pad0, data.sunRaw.pad1, data.sunRaw.pad2, data.sunRaw.pad3

];}

What does the new code really do? First we flatten the incoming data, remember, we will still get the data slices from the server. The flattenData function just arranges the data in a flat array. We then add the current time to every data point, just for convenience. Finally we simply add the new values to the correct arrays one by one.

To access the data now we don't use a dataFilter anymore but instead just the indices of the array. For clearness I could (should?) have used an object as result of flattenData but the array will do just fine:

const accelSinks : Sinks = createGraph({

heading: 'Accelerometer',

yScaleText: '',

dataIndex: [0, 1, 2]})(sources);

Step 6: Enjoy again! ...What, still bad?

If you run the code again it is only slightly better. It runs about 5 seconds smooth and then it starts jerking and in the end the browser will be overloaded again. There has to be another problem.

Step 7: Make it better (again)

If we think again we can identify another problem. We are choking the renderer! Right here:

const path$ : Stream<VNode[]> = scaledData$

.map<string[]>(data => data.map(arr => line<DataPoint>()(arr)))

.map<VNode[]>(lines => lines.map((s, i) => {

return <path

d={ s }

stroke={ colors[i] }

class-path={ true }

/>;

}));Every time we get new data (again, three times a second) we are changing the d attribute of the path element. This forces the browser to recalculate the layout of the element, its positon, coloring and a bunch of other stuff. Take that times the number of lines we have (21 in our case) and the reason why our renderer - and finally the browser - falls to its knees is clear.

But what can be do about it? I don't want less updates, because then the graph would be jerking too. Does that mean I have to live with that? But other people can make it work too!

Let's make a new version.

This requires a trick. We will still update the state as soon new data has arrived from the websocket. But we will only re-render the DOM in a fixed interval. Let's start with half a second. Because we will now use time based operators we will pull in @cycle/time that provides us with the necessary methods.

const updateDOM$ : Stream

.mapTo(undefined);const scale$ : Stream

.compose(sampleCombine(state))

.map(([_, s]) => s)

.map(s => ({

x: scaleTime()

.domain([secondsAgo(2), hoursAgo(0.04)])

.range([0, 2000]),

y: scaleLinear()

.domain(getDomain(s.domains, info.dataIndex))

.range([0, 400]),

state: s

}));const scaledData$ : Stream<DataPoint[][]> = scale$

.map(scales => [scales, selectData(scales.state.values, info.dataIndex)] as [Scales, [Date, number][][]])

.map(([scales, arr]) => {

return arr.map(data => data.map(d => [scales.x(d[0]), scales.y(d[1])] as [number, number]));

});So far so easy. But why are we setting the leftmost value to a time in the past? Why not to the newest date anymore? That way the newest data will be hidden!

This has a simple reason while we can't rerender the whole graph, we can move it. Every SVG element accepts an attribute named transform. With this attribute we can rotate, scale or translate - move - the element. As this is using GPU acceleration we can do it as often as we want!

const group$ : Stream

.mapTo(undefined)

.compose(sampleCombine(scale$, path$))

.map(([_, scales, paths]) => [scales.x(new Date) + 15, paths])

.map(([v, paths]) => {

return svg.g({

attrs: {

transform: 'translate(' + (-v) + ', 0)',

}

}, paths);

});We use @cycle/time to give us an stream of animationFrames. Those signal that the browser is ready to accept new draw commands. We then use sampleCombine from the xstream extra operators to combine it with the current scales and the current paths. The main difference between combine and sampleCombine is that the former emits when any stream emits, the ladder only when the main stream emits.

Step 8: Enjoy! Finally!

If you run it now in the browser you see butter smooth plots of the newest data.

Step 9: Still not enough?

What can we do to increase our performance even more? These are just ideas for the future, I might implement (some) of them.

Immutable.js

We already use immutable data structures. When the data of the websocket is added to the state we always create new arrays. But this is costly, especially as the arrays get bigger. Here using Immutable.js can help a lot. Instead of using a normal array, we will use a List.

What is the advantage? Consider the structure of a list vs an array:

List Array

a -> b -> c -> d [a, b, c, d]

When we add a new element to the front (or back depending how you look at it) we just have to create one element that points to the first element of the old list (we run in O(1)). If we add an element to the array, we have to allocate a new array and copy all elements from the old one to the new one (we run in O(n) plus we have n new allocations).

This technique is called structural sharing.

Pausing unused graphs

We currently have seven graphs. They do not fit all on your screen. So we could use a periodic check or a check on scroll if the graph is even visible. If not we can pause the whole rendering process. We could make use of jQuery's :visible pseudo selector.

This way we have only between three and four graphs active at any time (plus/minus one depending on screen size) so we cut about half of our rendering time!

Step 10: UI/UX goodies

As with the previous point these are ideas for the future, I might implement some of them.

Proper scales

The scales on the y axis you can see in the current version are generated using d3-axis-hyperscript, a library that was hacked together by me in an hour. That's why it is not working very well and I would not trust the axis too much. I basically took the idea from d3-axis and made it work without direct DOM manipulation, but with normal snabbdom vnodes instead.

We could add something like helper lines to make graphs clearer and achieve API compatibility with d3-axis. And fix the remaining bugs of course. If someone is interested, PRs are welcome :)

Resorting the graphs

As we can only see a certain number of graphs on the stream at a time, it would be very nice if we could reorder them. That way we can bring the graphs we are interested in closer or near each other allowing you to see them at the same time.

This is fairly simple to achieve. I created cyclejs-sortable that fits exactly this use case (shameless plug, again). With this we can just add a font awesome symbol to each graph that we can use as handle. We can then use this handle to reorder the graphs with drag and drop.

Closing it up

All source code is on GitHub. This is a copy of the original repo, so you can go back a few commits and see the original history.

For the purpose of this article, I updated the repo to use the newest Cycle.js version - Cycle.js Unified - and I removed the dependencies on other programs we use to get the data off our satellite hardware. The current master generates random values and sends them to the client. You can see all changes here.

Jan van BrüggeDeveloper

Jan van BrüggeDeveloper